Concerns are growing across UK university campuses that mobile phone apps used to record attendance could be used in surveillance and to potentially even wrongfully deport international students.

Since Covid, universities have increasingly adopted mobile phone software that students must download, allow to track their location, and use to mark their own attendance by entering a one-time code when they arrive at class.

One of the main reasons that universities introduce these digital check-in apps is to prove to the Home Office that international students are at university, and to report people to immigration authorities if they are not.

Some students and staff at universities that have adopted these apps are worried that they could put international students at risk of wrongful deportation.

Dr Lucy Mayblin, a political sociologist at the University of Sheffield and expert on UK migration, said: “International students are in an Orwellian situation. The idea that these apps are impervious to human flaws is a complete myth. The apps are just a faceless computer. Students are getting trapped in the system which doesn’t care and is oriented to deporting them.”

Student deportations based on bad data have happened before. After a BBC Panorama documentary in 2014 which revealed cheating by some international students in English language tests, thousands of them were wrongfully accused and forced to leave the country. There are fears it could happen again.

“The stakes are really high for international students,” said Dr Mayblin.

The pressure is also intense on universities to provide data to the Home Office, because they risk losing their visa license to sponsor international students if they fail to keep up with Home Office requirements. The consequences of losing sponsorship status would be dire for universities, who are financially dependent on international tuition to balance the books.

The University of Sheffield is one of the many schools that have started using an attendance app to streamline their reporting to the Home Office.

Andy Winter, Director of Student Support Services at the University of Sheffield, said: “We launched a digital check-in tool to make recording student attendance faster, easier and more consistent across the University.”

Universities say that these apps also make it easier to identify students who may be struggling with their coursework and might need extra support.

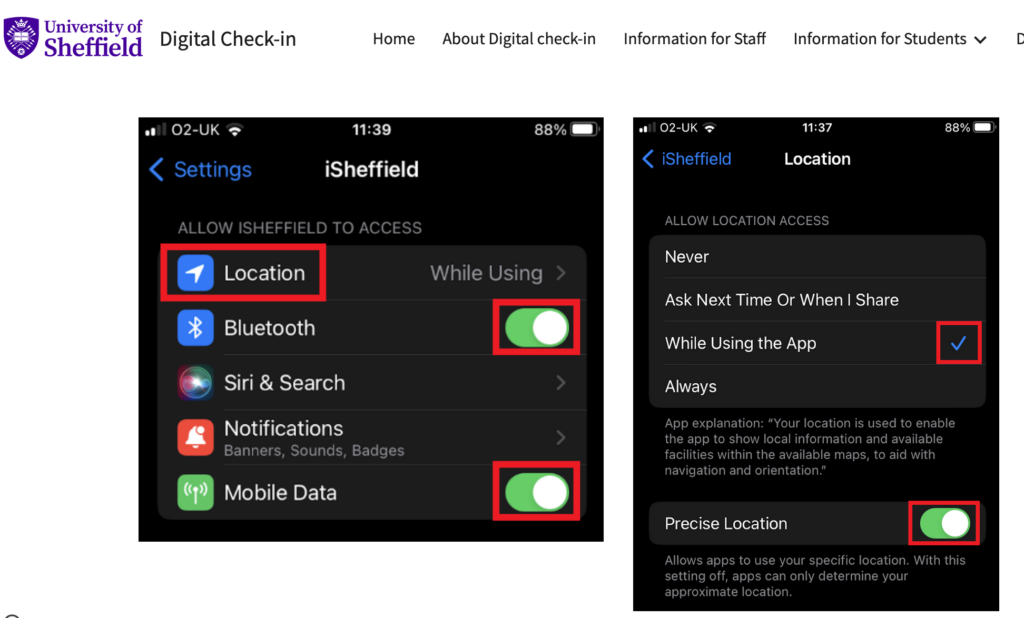

In January, the university started requiring both UK and international students to check-in to class on iSheffield, an app which uses software licensed from Israeli company Ex Libris.

If location tracking on students’ phones is set to ‘always’, Ex Libris is able record and store data on the whereabouts of them everywhere they go. Ex Libris operates attendance apps for at least 11 UK universities, and is only one of several companies providing similar services across the country.

For some international students, the new app is making them feel even less welcome in the country than they already do.

“I don’t feel like a human being, I feel like a number. Why can I be tracked 24/7 by my university?” said Jonas, an international student at the University of Sheffield. Jonas, who is gay and from the Middle East, asked to use a pseudonym for protection from anti-LGBT discrimination in his home country.

He said: “The fact that my university, who is supposed to help students find their voices, is instead tracking us… That says a lot.”

Student activists at the University of Bristol and Goldsmiths, University of London, have recently staged boycotts against the check-in apps at their schools. “The controlling and monitoring of our locations is fundamentally an affront to our freedom of movement as well as a threat to our privacy,” said Student Action Bristol.

The University of Sheffield has told staff that it will not use the geolocation data for anything other than check-in verification. Rachel Scheer, a spokesperson for Clarivate, the parent company of Ex Libris, said: “All Clarivate products operate strict data security protocols and the data within our apps is only available to the university or institution who licensed the app.”

Some staff, however, continue to question if this is the case for international students. Dr Annapurna Menon, an associate lecturer in Politics and International Relations, said: “We don’t want to be complicit in deporting our own students. We haven’t gotten any assurance from the university that if the Home Office demands specific location data, will the university refuse? We are educators, we are not the police.”

A wide variety of technical issues are also causing distress for international students struggling to get their attendance recorded accurately. Like many students at the university, Jonas regularly struggles with technical problems: “What if my phone is dead and I turned up to lecture? Multiple times I would be in a building with no service and I wouldn’t be able to check in.

“The reports that we’ve gotten from students is that the app is really fallible,” said Colombian international student Maria Jose Lourido, education officer at the University of Sheffield Students Union.

“A lot of students say that lecturers are not putting up the attendance codes, that the app is not properly tracking them when they’re in the room, that the codes are not working, that the app is slow. The university cannot come in and make sure the internet across campus is excellent, so where the internet is not strong, it will fail.”

Mr Winter said the university is attempting to resolve the issues: “The option to be checked-in by a lecturer also remains for anyone who experiences any difficulties or cannot access the app.”

Ms Jose Lourido says that isn’t a solution: “When the university tells international students that they have to register their attendance or they’ll have immigration problems, the students have to spend 15 minutes, when they have class, saying to the lecturer ‘please, I’m trying to log on but it’s not working’.”

Despite the issues with the attendance taking app, teachers and students interviewed for this article all agreed that some form of attendance taking is a good thing.

Imad Tak, an international master’s student studying data analytics, sees benefits to the app: “People are forced to come to the classes, and it’s good to have students in lectures.”

Many suggested alternative ways to take attendance. Most of the people interviewed for this article prefer a system where students would scan their ID cards at card readers installed in classrooms, which would reduce technical issues and prevent universities from giving location data to outside companies. “We have university ID cards – why are we not using ID cards when we already have them?” said Ms Jose Lourido.

Dr Menon, who teaches classes in the politics department said: “We already were able to catch if students were falling through the cracks with our earlier attendance system when teachers recorded attendance manually. We could go back to that.”

The Home Office’s student visa sponsorship guidelines do not actually require universities to report attendance, only to prove that they have a “a single academic engagement policy that applies consistently” to all students. This could include data showing any combination of proof that students are submitting coursework, doing research or laboratory work, and attending classes.

Mr Tak suggested a big rethink for universities trying to maintain their visa sponsorship status: “Rather than focusing on student attendance, universities could focus on our grades.”