As Asian hate crimes soar, understanding the community has never been more important.

Last week’s events in Atlanta sent a wave of terror through the ESEA community, both in the US and around the world. A man’s shooting spree across massage parlours in Georgia killed eight people, six of whom were women of Asian descent. USA Today unveiled the personal stories behind each of the tragic victims, who were hard workers, dedicated mothers and business owners. This racist hatred is not new, nor is it only prevalent in the US.

According to the advocacy group End the Virus of Racism, there has been a 300 per cent increase in hate crimes towards people of East and Southeast Asian heritage since the start of the pandemic. In February 2020, international Singaporean student Jonathan Mok was assaulted so badly he needed surgery. In broad daylight. This escalation of attacks led to the trending hashtag #StopAsianHate – both a collective gesture to show solidarity within the ESEA community, and a plea to the world to lend support in the anti-racism movement.

These hate crimes, spurred on by racist rhetoric from politicians like Donald Trump, project Asians as monolithic. Stories by people of Asian heritage, from East and Southeast Asia to the Pacific Islands, provide a much-needed window into their lives, emotions and experiences. This piece brings to the fore books which illuminate what it is to be East and Southeast Asian, dispel the clichés and change the cultural narrative – currently so saturated with outdated stereotypes – one story at a time. To read them is to begin a journey of allyship, which is needed now more than ever.

View this post on Instagram

Go Home! – edited by Royan Hisayo Buchanan, foreword by Viet Thanh Nguyen

This collection of works explores the meaning of “home” through an array of fiction, poetry and memoir. Published in collaboration with the Asian American Writers’ Workshop, the book complicates the idea of home as a physical place, and instead shows how its meaning can be found in food, relationships, journeys and language.

While this reflection on home is a universal human concern, it becomes particularly dire for those whose identities make them vulnerable to the threat of never belonging. Like many Asian immigrants, our experience with racism has traditionally occurred through being painted as the perpetual foreigner, the yellow peril or brown terror, with unbreakable ties to a land of origin. The beauty of a home in storytelling is that it allows us to create a multiplicity of homes which no one can completely take away.

Image credit: AK Press

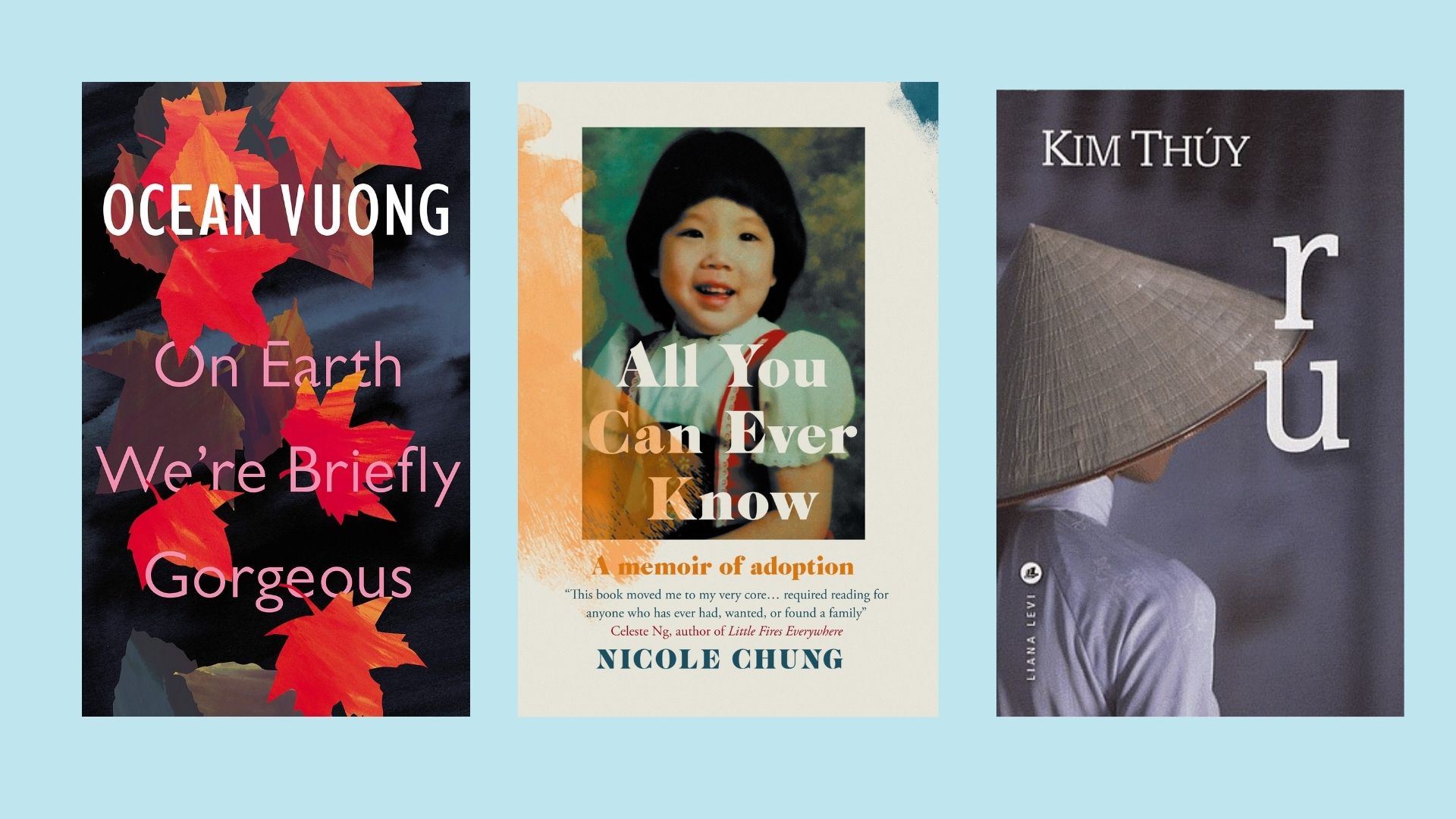

Ru – Kim Thúy

On a starless November night in 1978, crowds of Vietnamese people, including Kim Thúy, huddled aboard a storm-battered boat bound for Malaysia. Crouched in darkness, refugees became numb to the smell of urine, sweat and fear that engulfed them. Night and day became indistinguishable.

Thúy was ten years old when the Vietnam War ended with the fall of her hometown Saigon – old enough to recall the deathly silence that besieged the once-lively capital, and the transformation of red gao blossoms into bomb craters. Following the communist takeover of Saigon in 1975, a million so-called “boat people” like Thúy took to the oceans, braving the threat of not only starvation, but rape and murder at the hands of pirates. Ru is a work of autofiction, blending the author’s lived experience with fiction. Readers witness the immense hardships faced by the narrator Nguyen An Tinh, who, like Thúy, journeys from Vietnam to Canada, struggles to integrate into Quebec society, returns to Vietnam as a lawyer, and experiences motherhood. Watch the video below to hear more from the author.

All You Can Ever Know – Nicole Chung

What is it like for a Korean adoptee to grow up in a white family, couched in the American suburbs? In this searing but delicate memoir, Chung shares the personal decisions and compromises she confronts both as an adoptee and as a mother-to-be. Born very prematurely in 1981 to Korean immigrants, Chung was immediately adopted by white Americans, a doting couple from Oregon who, after so many years of trying for a baby, believed her survival and arrival with them was a “gift from God”.

The memoir’s greatest triumph is in its insistence on complicating the rescue narrative of transracial adoption without resorting to straightforward indictments of any particular worldview. While breaking the silence on her racial isolation and confusion, Chung teases out the limits of her adoptive parents’ race-blindness with compassion. There is joy; the adult Chung forges bonds with her biological sister and the pair experience motherhood in unison. There are unsettling revelations too, and her search for answers stirs anxieties familiar to us all. Rewriting race into the adoption narrative, Chung’s decade-long journey expands our language for exploring the disorderly margins of familial legacies.

On Earth We’re Briefly Gorgeous – Ocean Vuong

“‘On Earth We’re Briefly Gorgeous’ is a letter from a son to a mother who cannot read,” the blurb says. Expressing the pain and agony of the Asian experience is not just challenging in the wider world, it can be a struggle within our own families and communities too. In the Vietnamese-American author’s debut novel, Ocean Vuong captures the emotions and sacrifices of a poor immigrant family – along with the trauma of that journey handed down multiple generations – which are almost impossible to explain. The book begins during the narrator Little Dog’s childhood, as he collects fractured memories of his mother to share with her.

Vuong, who was born in Ho Chi Minh City before immigrating to Connecticut when he was two, untangles the threads of queerness, class, drugs, and depression which shadowed his upbringing. Each beautifully crafted sentence reads like poetry, inching us closer to Vuong’s voice, his feelings of shame and desire.

Portrait of Ocean Vuong in the playground behind the house where he grew up in Glastonbury, Connecticut in 2019. Image credit: The Atlantic.

The Kiss Quotient – Helen Hoang

This romance novel centres on Stella Lane, an autistic heroine who hires an escort in order to boost her confidence with sex, relationships and setting boundaries. The author, Helen Hoang, is of Southeast Asian descent and was diagnosed with Autism Spectrum Disorder as she was writing the book, aged 34. We are immersed in Lane’s triumphs and anxieties as she takes charge of her life and her sexuality on her terms, while also learning how to lean on someone for help, for support, for intimacy. In her quirky fun way, Hoang insists that there is power, and with it, agency, in self-love.