When Nataliia Ruda fled Ukraine with her family, she thought they would be away from home for a couple of weeks until Putin’s ‘sick joke’ was over.

With just one bag of clothes and a toothbrush each, Nataliia and her sons travelled through Romania and Slovakia before arriving in Lincoln, as part of the Homes For Ukraine scheme. She initially struggled to adapt as she navigated the language barrier and the stress of being so far from her home, but this was balanced with gratitude for those who stepped in to help her. “English people are very kind,” Nataliia says.

Russia’s invasion of Ukraine in 2022 generated Europe’s largest humanitarian crisis since the breakup of Yugoslavia in the 1990s, with 6.5 million people fleeing Ukraine. Another 3.7 million are internally displaced.

Two years later, some of those who fled are beginning to rebuild their lives. Despite leaving behind their homes, jobs, and in many cases their loved ones, they have found solace and a new form of normality.

Nataliia is one of 250,000 Ukrainians who have been granted visas to stay in the UK. They have had to battle not just the reality of their situations being far less temporary than first thought, but also PTSD, the loss of loved ones, and the media’s short attention span in the wake of the Gaza crisis.

For Tetyana Mykhaylyk, who moved to Sheffield from Ukraine over 20 years ago, combatting war fatigue is the most important thing. She has opened her house up to a number of refugees and in an effort to keep the conversation about Ukraine alive, she organises events to raise both money and awareness for those still in the country.

She says: “It’s really important to continue to talk about Ukraine. Nothing has changed. We have to keep doing things to give back.”

One of Tetyana’s friends volunteers as a chef in Lviv for 15 hours a day, preparing meals for the army. Another of her contacts recently sent her a photo of a cemetery in Kyiv which now dominates the landscape, hosting hundreds of war heroes who have sacrificed everything for their homeland. This does not crush the morale of those in the city, rather, it spurs them on.

Tetyana says: “It’s a sad picture, but the more lives lost, the more people will not accept losing the war. We have paid with the best lives. We really can’t see how we can lose because we will not live under Putin. There will be resistance from every last person.”

Some Ukranians who originally left their home have now taken the decision to return to the country, the strength of their yearning too much to resist. Nataliia Ruda’s younger sister, Yuliia, is one of them. After a few months in the UK, she and her partner returned to Kyiv despite the risks.

On a video call, Yuliia described a scene of anxiety, with rockets raining down on the city and planning ahead impossible. Appointments are frequently cancelled due to air raid sirens screaming through the streets for people to take shelter. Harrowingly, amputees have now become a growing demographic. Yuliia says: “People carry on because what can they do? We will continue to live.”

Nataliia misses Yuliia, but her experience of the UK has changed her outlook on the future. “I never thought I’d live in another country,” she says. “I love Ukraine. But now I love England as well. When the war finishes, I will visit my free country but I would like to stay here.”

After initially working in restaurants and a school, Nataliia now has a job she adores buying and selling seeds for one of the UK’s largest potato manufacturers. Through a huge grin, she says: “It fills me with ecstasy.”

Her two sons, Tim and Zhenia, are doing well in school, and the family are hoping the opportunity for them to remain in the UK will be offered. She says: “My life was hard in Ukraine. My husband left us and I worked in the casino on night shifts to look after my sons. Now, I feel more free. I am happy.”

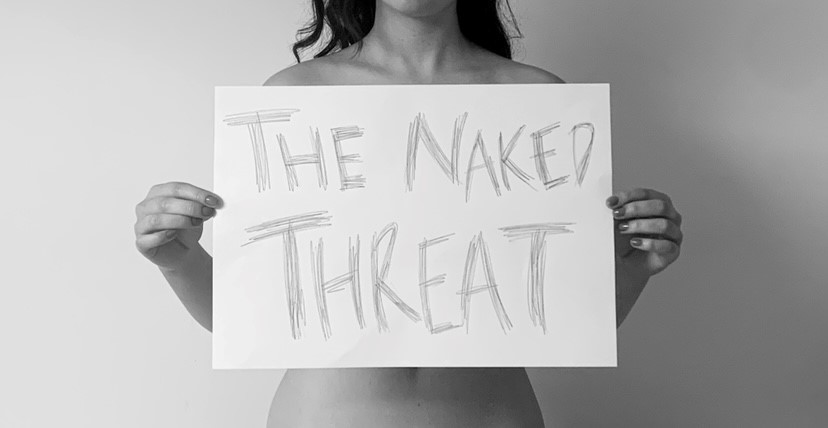

Nataliia’s newfound happiness and Tetyana’s community work are testament to the indomitable Ukrainian spirit that refuses to concede to Putin. What began as a three-day ‘special military operation’ to annex the state has evolved into a protracted stalemate. So far, 31,000 Ukrainian forces have been killed, in addition to a UN estimate of 10,500 civilian deaths.

A counter-offensive last summer led to President Zelenskyy winning back a handful of villages, but the conflict has largely become a war of attrition across a brutal but fairly static frontline in the eastern oblasts. The hope of a rapid victory on both sides has transformed into an extended episode of history.

Yesterday (March 3), Zelenskyy renewed his pleas for more weapons, fearing the West’s waning focus is costing his countrys chances of success.

As the war enters its third year, there will be millions wishing it will be its final one. That hinges not just on the Ukrainian resilience, but on the West keeping its attention on the conflict too.

As Tetyana, who is determined her home country doesn’t disappear from the public consciousness, says: “It really makes a difference to people knowing they’re not forgotten.”