Greaves backs decision to snub Ally Pally

Beau Greaves has defended her decision to choose Lakeside over Alexandra Palace this year as she aims for back-to-back world titles.

The 19-year-old from Doncaster, nicknamed ‘Beau 'n’ Arrow’, chose to defend her WDF Women’s World Darts Championship title in Surrey this week instead of entering the PDC World Darts Championship, which begins in London next week.

This was following the PDC’s decision to prevent players from competing in both tournaments back in September.

Speaking to TungstenTales after her first-round win over Lorraine Hyde on Monday, she said: “This is a ladies’ world championship, it’s got that name on it. The PDC one doesn’t, it’s a men’s world to me.”

Greaves cruised to the Quarter-Finals of the tournament after a 2-0 victory over the Scot. She is due to face American Paula Murphy this evening.

Greaves’ decision to snub Ally Pally in favour of Lakeside this year has led to much debate across the darts world.

Former BDO World Champion Mark Webster admitted Greaves was taking a risk in her choice.

On the Love the Darts podcast in November, he said: “Whether it is the right decision or not, I don’t know.

“It’s a gamble. There’s £25,000 up for grabs for winning [at Lakeside]. There’s never a guarantee, but she’s a big front-runner.”

Greaves was, however, defended by fellow competitor Fallon Sherrock.

Nicknamed the ‘Queen of the Palace’, Sherrock rocked the darts world in 2019 after becoming first woman to take victories at the PDC tournament.

Speaking to Live Darts TV, Sherrock – who chose Ally Pally over Lakeside – said: “I completely understand her decision. She wants to be multiple world champion, and whilst she’s got the game, go do it!”

The WDF World Darts Championship Finals take place this Sunday, whilst the PDC World Darts Championship commences next Friday.

Sheffield’s Clean Air Zone successes overshadowed by faulty bus technology

Fewer of the most polluting vehicles were recorded in Sheffield's Clean Air Zone over the past year, but faulty technology in diesel buses has failed to meet emissions standards.

The first Sheffield City Council report showed between November 2022 and October 2023 the number of the most heavily polluting HGVs, buses and taxis fell by two-thirds both within the CAZ and across the city as a whole.

But catalytic reduction technology retrofitted in the city’s buses is failing to perform at the desired standard for reducing emissions.

In a statement to Parliament on Tuesday, Paul Blomfield, Labour MP for Sheffield Central, said: “The main problem with the retrofit devices running in urban areas is that they do not reach the required temperatures to treat emissions as a result of the regular stop-start conditions.

“That happens significantly when buses run downhill, and anybody who knows Sheffield knows that there are a lot of hills to run down.”

Altogether 75% of the city’s 400 buses have been retrofitted with the technology, but still do not comply with the desired Euro 6 standard.

The remaining 25% have had no technology installed and so still release the same levels of harmful emissions.

Mr Blomfield is now imploring the government to fund the roll-out of hydrogen and electric buses in Sheffield.

The CAZ was introduced in February to tackle Sheffield’s dangerously high levels of nitrogen dioxide, which contribute up to 500 deaths per year according to a 2010 NHS report.

Despite failures with the buses, the data shows Private Hire Vehicles are now 96% compliant compared to 77% before the CAZ was launched and LGVs are now 84% compliant up from 59%.

Cllr Ben Miskell, Chair of the Transport, Regeneration and Climate Committee, said: “Hundreds of people in Sheffield die prematurely each year due to air pollution, cleaning up the quality of the air we breathe around Sheffield is rightly one of our top priorities and this data shows that motorists are helping by moving to cleaner vehicles in response to the Clean Air Zone.”

The CAZ currently fines highly-polluting lorries, vans, buses and taxis that drive within the boundary of the ring road, with charges ranging from £10 per day to £50 per day depending on the vehicle.

The scheme does not apply to private cars and motorbikes.

In November, the council announced the CAZ had currently raised over £3m in charges and fines for late payments.

However, this still falls short of its £4.25m implementation cost.

Fitzpatrick stands firm in Morikawa penalty controversy

Sheffield’s Matt Fitzpatrick has doubled down on the decision to penalise Collin Morikawa at last weekend’s Hero World Challenge.

Morikawa dropped from -10 to -8 before he began his final round at Albany Golf Club in the Bahamas, following intervention from playing partner Fitzpatrick.

One-time Major winner Fitzpatrick explained Morikawa’s caddie, Jonathan Jakovac, used a device while on the practice green before the American’s third round to calculate slope.

Mr Jakovac then breached R&A Model Local Rule G-11 by recording this information in his yardage book. Chief referee Stephen Cox was made aware of the incident after the Sheffielder asked him for rule clarity.

According to GolfMonthly, Fitzpatrick said: “It’s nothing personal. Whether it was Tiger [Woods] or whoever, it’s just I wanted to know because I have wanted to use AimPoint [a putting statistics technique] earlier this year.”

Fitzpatrick finished tied for fourth at Albany on -15, with Morikawa seventh on -12. Fellow American Scottie Scheffler took victory in the Bahamas, finishing on -20.

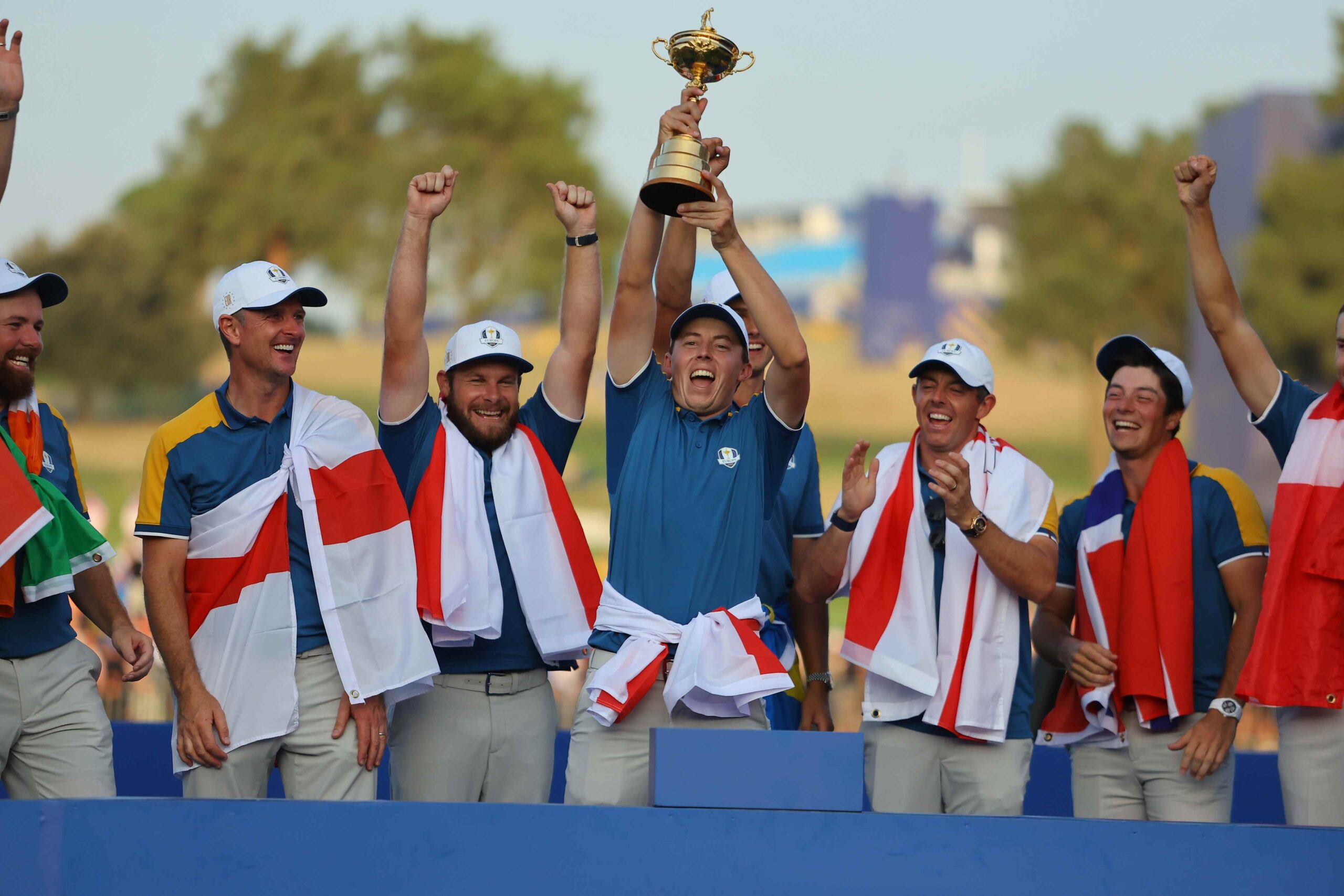

The tournament built on a strong year for the Sheffielder. Fitzpatrick won the RBC Heritage back in April along with the coveted Alfred Dunhill Links Championship at St Andrews in October.

He was also part of Luke Donald’s European team who regained the Ryder Cup at the end of September.

Rotherham identified as an area of “particular consideration” for child exploitation

The town has been highlighted as needing attention in a new report released today by His Majesty’s Inspectorate of Constabulary & Fire & Rescue Services (HMICFRS).

The report details the extent of the failings by public services, with the scale of child sexual exploitation and abuse in the town attracting a “great deal” of public attention.

A 2014 independent inquiry into child sexual exploitation in Rotherham, commissioned by Rotherham Metropolitan Borough Council (RMBC) found that at least 1,400 children had been subjected to serious sexual abuse in Rotherham between 1997 and 2013.

Collective failures by RMBC and South Yorkshire Police (SYP) were identified, with Dame Louise Casey DBE CB’s investigation into RMBC in September 2014 finding a Council “in denial”.

The report, presented to Parliament in February 2015, concluded that child abuse and exploitation was happening on a national scale, but that Rotherham was different in that “it was repeatedly told by its own youth service what was happening and it chose, not only to not act but to close that service down".

An independent criminal investigation by the National Crime Agency (NCA) into non-familial child sexual exploitation in Rotherham between 1997 and 2013 began in December 2014.

This investigation is currently in its ninth year and has cost approximately £70m.

HMICFRS said as part of their inspection, they found there was a well-established, multi-agency safeguarding approach between South Yorkshire Police and its safeguarding partners for responding to child sexual exploitation.

A member of a safeguarding children partnership in South Yorkshire said: “You have to dig to find child sexual exploitation and group-based child sexual exploitation.

“In Rotherham, we work with the police and when we dig, we dig together.”

Despite changes being evident, HMICFRS claims lessons aren’t fully learnt.

A clear definition of group-based child sexual exploitation is not apparent, with HMICFRS stating this “creates difficulties when trying to assess the nature and scale of offending".

Shortcomings were identified when it came to the way the police “identified, measured and analysed data and exchanged information with each other about group‑based offending".

In April 2023, the government announced their intention to establish a new child sexual exploitation task force. The impact of this remains to be seen.

£15m Mexborough orthopaedic centre on track to welcome first patients next month

A new orthopaedic hospital is on schedule to finally open its doors in the new year after nearly three years of development.

The Mexborough Elective Orthopaedic Centre of Excellence will open at the Montagu Hospital site at a cost of £14.9 million.

It is hoped that the new facility - which was constructed entirely off-site - will reduce waiting times for residents of South Yorkshire, with 2,200 procedures expected to take place within the first year of operation.

Mr Ranjit Pande, Clinical Director for Trauma and Orthopaedics at Doncaster and Bassetlaw Teaching Hospitals (DBTH) said: “This is a wonderful development for the people of South Yorkshire, and a testament to our commitment to work together, as providers across the region, to do our very best for local patients.”

The site will feature two state-of-the-art theatre units, two anaesthetic rooms and a recovery suite, in addition to 12 inpatient beds, and the procedures available at the MEOC will include hip and knee replacements alongside foot, ankle, hand, wrist, and shoulder surgery.

Gavin Boyle, Chief Executive at NHS South Yorkshire, said: “We are working hard across our system to reduce the time that our patients are waiting for operations. This investment is extremely welcome and will provide us with a fantastic facility that will give people from across South Yorkshire better and faster access to services.”

The project commenced planning and development in late 2021, and construction work commenced in July 2023 with an anticipated handover date of mid-December and an opening date of early January 2024.

Jon Sargeant, Chief Financial Officer at DBTH and Senior Responsible Officer for the project, said: “The MEOC is a testament to our commitment to enhancing patient care and reducing waiting times for orthopaedic procedures. This collaboration marks a significant milestone in our efforts to improve healthcare services in South Yorkshire.”

The facility was constructed almost entirely off-site, with 90% of the project completed before being transported to its permanent location in September, and will be open 48 weeks across the year.

Four people arrested in Sheffield and Rotherham on suspicion of Modern Slavery involvement

Police have arrested four people on suspicion of Modern Slavery concerning sexual exploitation in the Dinnington area of Rotherham.

A 45-year-old man and a 37-year-old woman from Dinnington, Rotherham, were arrested and a 58-year-old woman and a 37-year-old woman from the Manor area of Sheffield were arrested after a warrant was executed.

The arrests and warrants took place in their residential addresses.

Detective Inspector James Smith from the Modern Slavery Team said: “Modern Slavery is occurring within our communities across South Yorkshire and information from members of the public is crucial so that vulnerable people who are potential victims of exploitation and locations of concern can be identified.

"We are determined to keep people safe and pursue those who exploit people through Modern Slavery and Human Trafficking.’’

Investigating Officer Emma Halton said: “If anyone has any information which could assist us with our investigation, please contact us online or by calling 101. Please quote incident number 759 of 1 September 2023, when you get in touch. Any information provided to the police will be taken seriously and reviewed and investigated thoroughly.”

Rachel Medina, CEO of The Snowdrop Project, said: "Modern slavery is prevalent in the UK, and within South Yorkshire-hidden in plain sight.

"It is vital to disrupt and prosecute perpetrators, and also offer appropriate, meaningful support to survivors of this horrific crime so they can recover and rebuild their lives.”

The Snowdrop Project is a South Yorkshire-based charity providing support to survivors of modern slavery and exploitation.

If you suspect someone may be at risk or have any information which may relate to Modern Slavery or Human Trafficking, please report it to the police or via the Modern Slavery Helpline on 0800 0121 700. Any information provided to the police will be taken seriously and reviewed and investigated thoroughly.”

Bleak Christmas ahead for Sheffield’s Ben’s Bazaar as building declared unsafe

A well-known Sheffield charity shop may be forced to close in the new year if donations and customer spending do not increase.

Danny McDonald, Ben’s Bazaar’s Information Hub Officer, said: “The fire service came in to do a routine check, after looking around, they discovered that the building wasn’t safe.

“They shut us down with immediate effect and gave us a prohibition order saying we can’t trade from here."

Ben’s Bazaar's old store on Rockingham Gate is run by Ben’s Centre, a charity providing a safe space for people struggling with substance abuse.

Their new stall at Moor Market is failing to bring profits.

The charity was not paying rent for the store, receiving help from Community Spaces, an organisation who link together charities who need space and landlords.

They need to find somewhere with very low or free rent to make ends meet.

Mr McDonald said: “We looked around at options after the closure, and the only one we could find was the market."

“It’s not a long-term solution, simply because we are not selling enough stuff there unfortunately. We are running it at a loss and it looks like we may be shutting down in the new year."

People have assumed that the store has completely shut leading to a drop in their donations.

Mr McDonald said: “People weren’t just coming in to go shopping, they were coming to have a chat as well. There will be a lot of people who miss that."

The old Rockingham Gate store and help desk still serves as a registered safe space for vulnerable people in Sheffield.

However, it looks unlikely that the charity will have use of this building for much longer.

The charity is contracted to keep the building until next June, but the landlord can give a month’s notice at any time.

Mr McDonald said: “We’ve been kept in the dark about what’s going on with the old building, but it looks like the repair work will be too much money for the landlord."

Mr McDonald urges customers to donate between now and Christmas to keep them open for longer.

Ben’s Bazaar is open for donation drop offs from 9:30-3:30 on Wednesday to Saturday at 1 Rockingham Gate.

The charity also welcomes cash donations through their website.

To get in contact with Ben’s Bazaar about volunteering opportunities or donations, email nicky@bensbazaar.uk.

Sheffield street campaigns to get first ever tree

The first ever tree could be planted on an Arbourthorne street as a community fundraising campaign looks set to reach its £420 target.

The campaign was organised by Richard West through the Trees for Streets charity and aims to bring environmental and mental health benefits to residents on Hallyburton Road on the Arbourthorne estate.

Mr West said: “If you have more access to green spaces, you’re more likely to exercise and there’s an established link between exercise and mental health benefits.”

A study by Cardiff University on green space access and wellbeing during the Covid-19 pandemic shows a clear link between a short walking distance to public greenery and self-rated health.

Trees also improve air quality by absorbing pollution from cars and industry as well as helping to keep streets cool by providing shade during the summer.

The campaign has been a year in the making and was inspired when Mr West was walking home from work in Broomhall and noticed the difference in temperature between the leafy suburb where works and his street.

He said: “It took me almost a year to notice that there weren’t any trees, it’s not actually something that unless you deliberately think it comes to mind.”

“Sheffield claims to be one of the greenest in Europe but actually I find it's quite unequal, where I live there are no trees on my street or in the immediate area.”

If Mr West’s campaign is successful, a 5-10 year old tree will be planted on the street by Sheffield council contractors who have surveyed the area to ensure the tree will be safe and not obstruct pavements for residents.

The involvement of the council in the project has been contentious among people Mr West has discussed the campaign with due to persisting ill-feeling around issues such as the tree felling protests.

Mr West said supporting projects such as his could be a way to win residents’ trust back for the council and that their help could reduce the cost of trees by applying for central government funding.

He said: “No one wants to give money to the council so I’ve had this question when I’ve been speaking to the neighbours.

“They could subsidise trees for areas I’d argue probably need them more, an area like Arbourthorne could have a subsidised tree for example.

“I think they could be doing quite a lot in terms of building people’s trust, because obviously it takes time to do that.”

Mr West said he hoped if his campaign was successful it would snowball and inspire people in other wards who want more greenery in their area to do the same.

Just £15 from the fundraiser’s target at the time of writing he appealed to people to get the fundraiser over the line: “I think it’s a little vote for local politics. We can get lost in thinking about all the things in the world but this is something you can do.”

The deadline for donations is noon 11 December, the campaign donation page can be found here: Let's get our first street tree in Hallyburton Road - Trees for Streets

Man arrested on suspicion of murder released on bail

A 46-year-old man arrested on suspicion of murder this week has now been released on bail, pending further inquiries.

The man was arrested on the 4th of December after a 41-year-old man was found deceased at 2:38 pm on Leighton Road. His family has been notified.

A post-mortem examination to determine the cause of death was conducted on the 5 December 2023 but has proved inconclusive.

Police have said that investigations are still underway to determine the circumstances surrounding the man’s death.

Anyone with information should contact the police by calling 101 and quoting incident number 456 when getting in touch.

Alternatively, contact Crimestoppers anonymously on 0800 555 111.

Disabled campaigner slams Sheffield streets as vulnerable people are forced into road

The lack of dropped kerbs and disabled parking in Sheffield has been branded “horrific” by a disability support group.

After suffering a stroke, Liz Kieran, 39, uses a wheelchair and mobility scooter and frequently faces obstacles on pavements.

She said: “It’s not just cars on the pavements, it’s bins, it’s general rubbish, and the lack of dropped kerbs in Sheffield is quite horrific.

After years of looking for a disability support group, Ms Kieran decided to start Disabled in Sheffield, a network aiming to “bring people together to help each other.”

The network is currently writing a letter to the council about dropped kerbs and taking photos to identify locations and show it is an issue across Sheffield.

Another member of the network who wishes to be known as Laura, 50, is an ambulatory wheelchair user.

She said: "Cars, overgrown hedges, broken pavement and bins are a constant problem. Dropped kerbs may be non-existent or not dropped enough.

"I often use the accessible parking outside the theatres and it never ceases to amaze me that there are no dropped kerbs alongside them. I have to drive into the road to access the pavement and my car."

Last year, the council banned cars from parking on pavements on over 20 Sheffield streets after facing increasing pressure from disability groups.

While good news to some, the ban means disabled drivers find it increasingly difficult to park in the city because of busy car parks.

Carolyn Young, 78, retired financial officer, relies on driving for longer distances because her mobility is affected by spinal stenosis.

Ms Young said one of the worst places to park is the Royal Hallamshire hospital which has replaced disabled bays on the approach road with concrete flower tubs.

She said: “The hospital does have a multi-storey car park with a small section on the ground floor with disabled bays. However, they are almost always full and I cannot go to a higher level because there is no lift, just a concrete staircase.

“[Sheffield council] are only interested in people using bicycles, walking or using public transport. I can't do any of these things. The disabled bays in the centre are few and far between.”

Andrew Jones, Facilities Director at Sheffield Teaching Hospitals NHS Foundation Trust, responded: “We appreciate that car parking around the Royal Hallamshire Hospital can be challenging for everyone at busy times due to the location of the building.

“We currently have a number of spaces reserved for blue badge holders at the Royal Hallamshire. These are located: outside the Minor Injuries Unit, on the ground floor in the Multi Storey Car Park and on A Road. We are also looking at increasing blue badge spaces in these areas in the near future.”

Sheffield charity offers £20 energy vouchers to help with cost-of-living crisis

High Green Development Trust is offering vouchers to people living across North Sheffield who are living in fuel poverty.

Those seeking a voucher will need to be referred by a professional such as social worker, GP, or teacher. Self-referrals can be discussed if you call into the Food Share or email referrals@hgdt.org.

Once referred, people can access one £20 voucher per month.

The Trust manages the campus, where people come to meet others, play sport, and access supportive services such as the Food Share and Community Fridge.

Lauren Sanderson, the Community Engagement Manager of HGDT, said: “Thanks to funding from South Yorkshire’s Community Foundation and the North LAC we can offer an energy voucher scheme this winter to residents on a pre-payment meter living in High Green, Chapeltown, Burncross, Ecclesfield, or Grenoside who are struggling with the cost of living.

“The scheme began at the end of November as the cold weather hit and will continue whilst funds last.”

According to Sanderson, in the first seven days of the service being available, energy vouchers have been distributed to six households.

In total, the scheme has helped 16 people, including 10 children.

HGDT also provides food and hygiene products through the campus food share located in the High Green community shop.

In the first half of 2023, HGDT supported 399 people with food and hygiene products who were struggling with the cost of living.

One anonymous service user said: “I've used the food share a few times this year as I have been struggling."

“All my bills are very expensive, and my food shop costs a lot more than it ever has. I work but I don't earn much. It just doesn't cover everything I have going out.

“Once the rent is paid, I don't have much left. The food share has been a real lifeline when it's been really hard to get from one week to the next.

“I was given some shower gel and things like that too which was good because they can be really expensive. The help has meant I had a bit less to worry about. I'm really grateful for the kind people here helping."

Find out how to make a referral for the food share, hygiene, and fuel support here.

Sheffield students to make their voice heard at COP28 climate rally

Students at the University of Sheffield have been painting banners and signs as they prepare to take part in a city-wide march on climate justice tomorrow afternoon.

The COP28 Rally has been organised by the South Yorkshire Climate Alliance and will see activists march through Sheffield from the Devonshire Green to City Hall.

Welfare and Sustainability Officer for the Student Union, Jo Campling, said it’s vital that students make their voices heard: “Student voice is essential and it’s so important that we take our future into our own hands.

“Students are super passionate but we’ve all grown up in a very difficult political time, but we do have a voice and we have to keep shouting, and I understand how challenging that can be and it can feel very bleak but we’ve got to do what we can.”

Adan Akhtar, 18, an Aerospace Engineering student from UAE, will be attending the rally on Saturday, despite also having an exam to sit that day.

Adan (left) and Jo (right) will be displaying their banners on Saturday (Source: Tom Burton)

He said: “Where I grew up we never had protests because they (UAE Government) literally just banned protesting, so I never really protested before, and after coming to Sheffield and seeing the fact that we can protest makes you want to join in and be there.

“When you see a lot of other students who are also there it gives you a bit of hope.”

The decision to host COP28 in UAE, a nation with vested interests in fossil fuels, has been met with criticism amid concerns the gulf nation plans to use the summit for political reasons.

While Miss Campling has been sceptical of the effectiveness of COP summits in general, she believes that students, and the general public, have to unite on such crucial issues.

She said: “I think that collective voice is hugely powerful and all big social change in history has come from mobilisation of people and protest and a range of other tactics.

“No one protest is gonna fix it, but it’s effective, and it’s fun and it brings hope to people and I think that’s really powerful.”

The rally comes in wake of the University recently placing 24th out of more than 1,400 institutions in the 2024 QS World University Sustainability Rankings, as well as 7th in the UK and 12th in Europe.

In November 2020, the University launched its sustainability strategy which aims to have a net-zero campus by 2030 and net-zero across all activities by 2038 and 100% renewable procured electricity on campus.

The rally will begin at midday tomorrow on the Devonshire Green, with students meeting on the concourse outside the union at 11.30am.