Roanna Van Os can still remember the dread she felt as a little girl when she was asked to act as an interpreter for her deaf parents. It made her feel different from her friends and stand out, at a time when she was desperate to fit in. “School was dreadful,” she says. “They always forgot to hire an interpreter for parents’ evening. They would trust me to translate everything and all the kids in my year would stare at me. I’d feel embarrassed and then guilty for feeling embarrassed.”

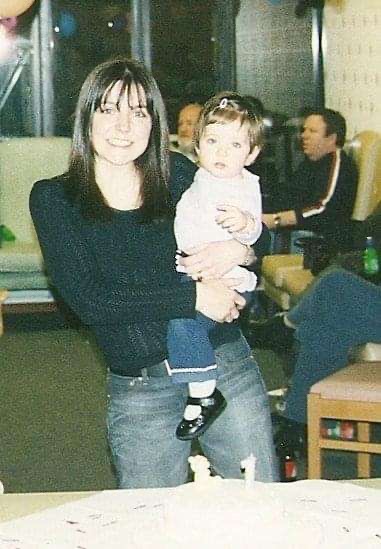

The daughter of two deaf parents, Roanna, 23, from Bury, Manchester, was forced to start interpreting for her parents when she was five-years-old. “My parents made me feel loved and supported, it was my other peers that made my life more difficult. It was always conversations I didn’t understand and my dad would get upset that people wouldn’t give him enough respect by simply writing it down or making eye contact. In most situations, I had to translate because the person my parents were trying to speak to would just look at me and ask me to translate because they were uncomfortable. My dad would then get really upset and was often called aggressive,” she says.

“When I was younger, people would demand to speak on the phone and they didn’t like to hire interpreters a lot of the time. To this day, I still have phone anxiety.”

It wasn’t just interpreting that made Roanna stand out. As a child of deaf parents, she was not used to regulating her voice, so would often get told she was too loud. “At sleepovers my friends parents would say ‘tell Roanna we’re not deaf like her parents’.”

The graphic designer believes the lack of understanding of the deaf community contributes to the ignorance people with hearing loss face. British Sign Language (BSL), is a language in its own right, but differs in sentence structure compared to English, and has its own grammar, syntax and lexicons, explains Sign Health.

“English is not a first language for my parents, BSL is, so like many deaf people they struggle with reading and writing. My sister Megan, and I, have to look over texts, emails and letters for our parents,” says Roanna.

Josefa Mackinnon also has deaf parents and explained she too had far more responsibilities as a child which resulted in her feeling isolated from her peers and forced to grow up very quickly.

“From the age of seven, having to call the bank or call the doctors, has a huge impact on how you’re brought up,” she says. ‘You’re involved in adult worlds before you really should too. I remember feeling, at the age of 11, that I was kind of older than my parents; that I had to be responsible for them.”

Although Roanna, grew up feeling as if she was a carer for her parents, she says her unique childhood had many positive elements to it too. “I love being a child of a deaf adult (CODA) and I’m proud to have deaf parents. My dad is highly respected within the deaf community. He speaks publicly a lot, something I can’t even do and he does it so well. He knows two different kinds of sign language and has a lot of charisma.

“My mum has a gentleness and taught me and my sister, Megan, to always be empathetic, something that I think does come with her disability. They both taught us to love everyone when growing up. I feel lucky to have grown up as a CODA because I don’t think I’d have the same emotional understanding otherwise.

“My communication skills are definitely better, especially when I go on holiday. Sign language teaches you body language and it makes it easier speaking to people,” she explains.

Both Roanna and Megan attended a CODA camp, run by an organisation, which was set up 13 years ago, offering support, refuge and a network for children with deaf parents. It hosts an annual camp for seven to 17-year-olds where children can participate in fun activities with other children with similar lived experiences.

“Coda camp really changed my life,” says Roanna. “At the time, I think I was 14 and I remember thinking ‘Oh my God why are they making me do this as a teenager’, but I had the most amazing time. I felt normal.”

Matthew Shrine, 34, CODA camp director, said: “It is the only national organisation representing solely children of deaf parents, where people can meet others with a shared experience.

“As a coda, you often have to filter yourself and as a kid you can feel misunderstood. I was called loud and abrasive growing up. But events like CODA allow me to be exactly that, and I realised oh wait I’m not odd.”

Mr Shrine, a therapist, also runs a CODA-specific therapy service to help those who find it difficult to share personal experiences with someone who doesn’t understand.

To find out more information about CODA go to https://www.codaukireland.co.uk/coda-camps