After widespread closures of specialist deaf schools, mainstream schools and councils have had to adapt learning environments to support the needs of more than 50,000 deaf children in the UK.

But with budgets being slashed and an increasing scarcity of resources, deaf education is facing neglect that 95% of teachers believe to be detrimental to the prospects of deaf children.

Deafness in itself is not a learning disability. This means with the right support, deaf children can – and do – achieve the same grades as their hearing peers.

Despite this, deaf pupils are on average 18 months behind their hearing peers, and achieve a grade less in each subject at GCSE.

Mike Hobday, Director of Policy and Campaigns at the National Deaf Children’s Society, says: “The overwhelming message from teachers across England is that the current system prevents them from helping deaf children to reach their full potential in school, which is a damning indictment.”

Integrated Units

Throughout the years, the number of specialist deaf schools has dramatically declined from over 100 to just 24. Shockingly, Wales does not have a single one, while options in the North and East of England are sparse.

This has left mainstream schools and councils responsible for integrating deaf education into standard learning environments. Integrated Units, such as those at Sheffield-based schools Lower Meadows Academy and Silverdale School, provide a lifeline.

Integrated Units are resource bases within mainstream schools which provide targeted support for deaf children. Funded by the Local Authority, specialist Teachers of the Deaf and signers provide bespoke lessons within the units that account for deaf children’s individual needs in subjects where additional communication is required.

The rest of the time, students are placed in mainstream lessons to enhance their independence and prepare them for later life in the hearing world.

Jane Dawtry, principal of Lower Meadows, says: “For any deaf children who can manage the demands of a mainstream school, I think this structure works really well for them because they get the best of both worlds. They get the support and they get to interact with hearing peers.”

However, the additional funding required to provide these services means they are restricted to children who have an Education, Health and Care Plan (EHCP). This accounts for just 20% of deaf children - mainly those with an additional need alongside their deafness.

Mrs Dawtry explains: “Per pupil funding has not changed dramatically in an awfully long time, yet the costs of staff and buildings have risen. So what you end up losing is your teaching assistants.

“When children absolutely need to have that support, that’s where budgets get very tight. The government needs to invest a lot more in the per pupil amount as a starting point for every school.”

These budget constraints mean there is an average of just one Integrated Unit per 200 deaf pupils in the UK, according to the National Deaf Children’s Society. Many regions, disproportionately in the north, have none.

Teachers of the Deaf

Schools without Integrated Units are not unsupported thanks to the vital role of Teachers of the Deaf. Not only do they support children with interpretation, they also assist teachers in understanding how to communicate and adapt their classrooms to be more inclusive.

Linette France is a Teacher of the Deaf and the Integrated Resource Coordinator at Lower Meadows. As well as academic work, Ms France also suggests general changes to the school which benefit the deaf. Under her guidance, Lower Meadows installed sound dampeners to prevent noise reverberation, such as heavy rain on the roof, from disrupting those with a cochlear implant.

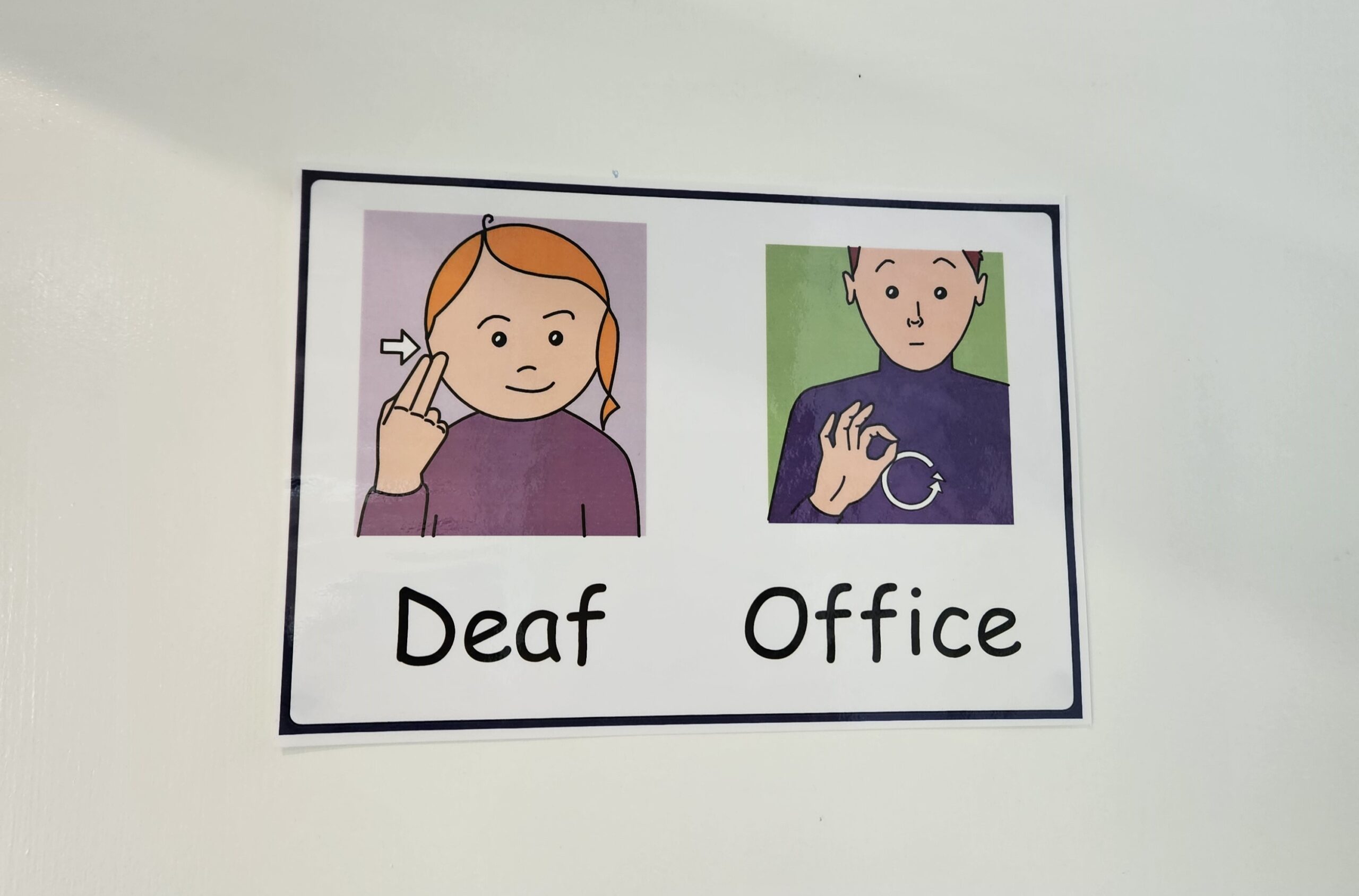

Ms France has found that the resources she uses to support deaf children also boosts the attainment of those with special needs. Using picture accompaniments with words and sign language can help autistic children process vocabulary, for example.

This is also true of non-native speakers. Ms France says: “Where their first language is not English, I have seen a massive turnaround in their English development because they've acquired English visually. It really is beneficial to everybody.”

Teachers of the Deaf can also educate hearing children to improve inclusivity with their deaf peers, such as through sign language lessons. Lower Meadows incorporates British Sign Language within their curriculum as an additional language.

Mrs Dawtry believes it has been a success story for inclusion, saying: “There are some children in the school who aren’t hearing impaired but can sign really well. When they get a certificate in assembly it’s really lovely, because all the children know that instead of clapping they need to sign.”

But for mainstream schools without Integrated Units, Teachers of the Deaf are not permanent members of staff, and are so stretched between locations that they are only available for a limited time each week. This means they cannot offer tailored advice and education at the same level as Ms France.

In Leeds, 1014 deaf children live in an area with just two specialist units and 12 Teachers of the Deaf. This is a ratio of one unit per 500 children and one Teacher of the Deaf per 83 children. As those on EHCPs are prioritised, some deaf students without these plans have no access to a Teacher of the Deaf at all.

There is also the issue of Teachers of the Deaf becoming scarcer, with a decline of more than 15% in England since 2011. More than half are due to retire in the next 10-15 years.

A skilled role which is pivotal in including deaf children in education and the hearing community could be at risk of extinction.

The Attainment Gap

The National Deaf Children’s Society says deaf young people are consistently failed by the education system. They believe the educational attainment of deaf children is causally linked to accessing bespoke resources, specifically Teachers of the Deaf.

But a lack of access to these specialist services, the curtailed budgets needed to provide them, and the concentration of help on only a select few deaf children shows the attainment gap that still needs to be breached, particularly in deprived areas.

The charity believes the government is condemning deaf children to underachievement. Mr Hobday, their Director of Policy and Campaigns, concludes: “Failing to [address this] will leave thousands of deaf children to struggle on alone.”