Plants are capable of making even smarter choices about how to treat their friends and foes than ever previously thought, new research from the Universities of Leeds and Sheffield has found.

A study published last month in Nature found plants can choose to starve out parasites trying to steal sugar from them even while they attempt, as much as possible, to feed the white threads of friendly mycorrhizal fungi who intertwine with their roots.

“The paper is really exciting. It really surprised me at the end of the day that the plants are able to do that,” said Dr Katie Field, Professor of Plant Soil Processes at the University of Sheffield and author on the study.

Plants are not just roots, shoots, and leaves. To grow and prosper, plants also form intimate partnerships with friendly fungi who provide the plant with hard-to-reach minerals from the soil in exchange for the sugars and fats that the plant makes from the sun.

“These relationships between plants and fungi have existed since the dawn of plants growing on land. We’re talking 500 million years,” said Dr Field.

The partnership is essential to our planet’s ecosystem and climate.

Dr Field said: “A lot of the air that we breathe, it is because of the actions of these fungi in the soil around us. And that contributes to climate and weather patterns.”

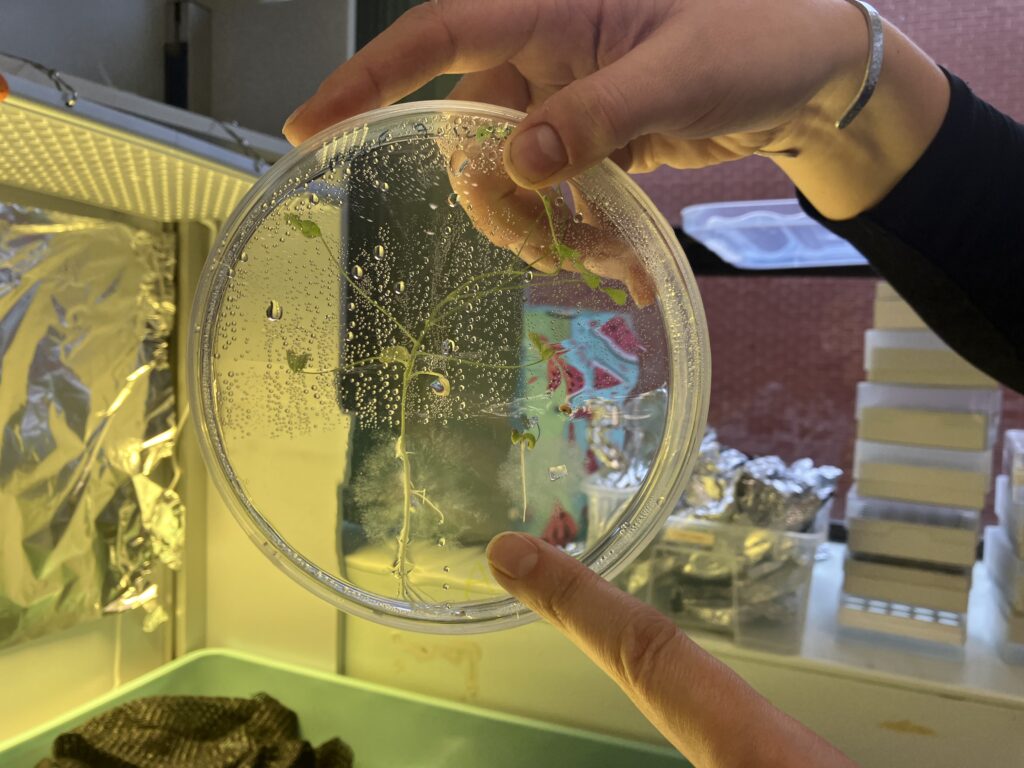

The experiment took place in glass houses on a roof at the University of Leeds. The fungi scientists took potato plants, split the roots in half, and planted half with mycorrhizal fungi, and the other half with tiny, squirming parasitic roundworms called nematodes. Then they let the potato plants grow.

When the scientists came back to the potato plants, they discovered the plants had cut off the supply of sugars to them both – but still kept pumping out the fats that fungi, but not nematodes, need as food. The fungi may not have gotten all the food they usually get, but they still got as much as the plant could provide without feeding the nematodes.

“Even in a situation where you have pests and diseases, fungi are going to provide huge benefits for the plant. What we did was show how,” said Dr. Field.

The new discovery could help farmers and food scientists develop new crops that maximise the benefits of friendly fungi – leading to healthier food and less need for pesticides.

“It’s good for soil, it’s good for carbon emissions, and it’s good for farmers pockets. There’s no downside to encouraging crops to form intimate relationships with fungi,” said Dr Field.