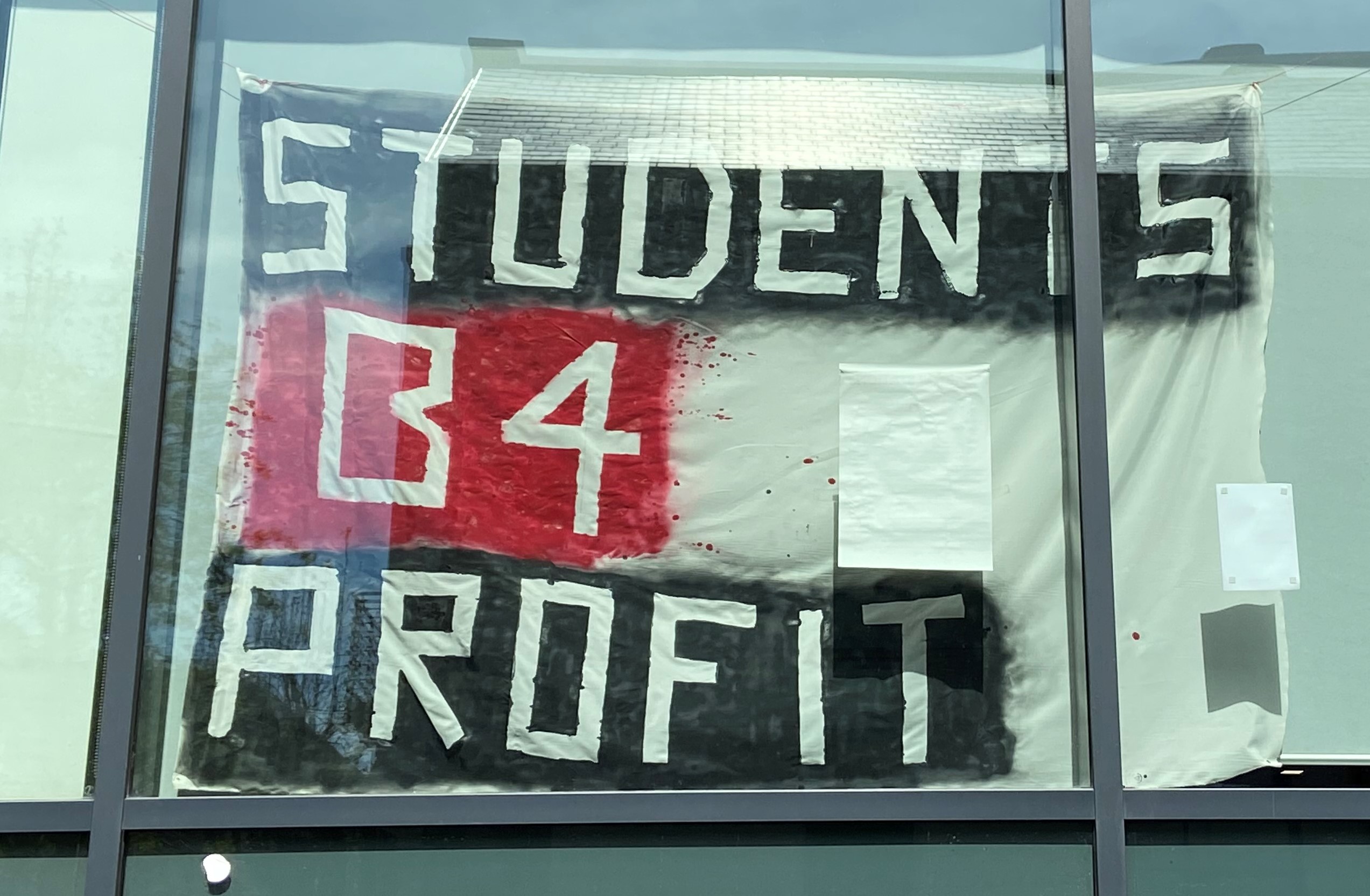

Credit: Kaye Fordtography

Jeans no longer fit the same way they did last March. Professional work wear consists of jogging bottoms for many. Even choosing an outfit to wear for the weekly grocery shop has become an anxiety-ridden task. Our relationship with our bodies has changed drastically over the past twelve months, but for many it’s become a balancing act between self-love and anxiety.

Navigating body image is a perpetual issue for women in our society, but Covid-19 has challenged our conceptions of ourselves and others spurring on both waves of anxiety and discoveries of self-love.

Prior to the pandemic, Kirsty Leanne, 28, ran a website encouraging plus-size travellers to improve their confidence, but now with travel plans remaining out of reach, she has had to adapt her message.

“I’m still working on building up content that educates and inspires people, but I have also started talking more and more about why people should live their life now,” the blogger said.

Ms Leanne uses her own experiences to encourage others to live the life they want now without waiting until they reach their ideal physique.

Credit: Kaye Fordtography

“The longer I kept waiting for the ‘perfect body’ the more my anxieties about travelling as a plus-sized person built up.” she said. The content creator spent a lot of her free time during lockdown thinking more about her body and working on unlearning toxic diet culture.

“I am trying to show people that they don’t need to lose weight before June 21st and that coming out of lockdown bigger than you went in shouldn’t hold you back from living your life,” Ms Leanne said.

A study by Anglia Ruskin University found that pandemic stress can be linked to a negative self-image and body issues. The research pointed towards increased intake of social media and comparisons to others as a source of anxiety.

For student Lauren Taylor, 19, the stress of the pandemic took its toll.

“I gained a lot of weight at the beginning of the pandemic due to ongoing health issues, not leaving the house, and eating out of boredom which made me feel rubbish.” Ms Taylor said.

With online workout trends sweeping social media, the university student became concerned that there may be new social expectations coming out of lockdown.

Credit: Lauren Taylor

Ms Taylor explained: “I thought everyone would be coming out of lockdown incredibly healthy, fit, and strong. As the pandemic continued and we entered the third lockdown, I started to appreciate that my body, in the state it is in, has gotten me through a bloody pandemic!”

Increased social pressures in the lead-up to summer are familiar for Evelyn Banks*, 22, whose name has been changed to protect her identity.

Ms Banks, who dealt with bulimia from 15-18 years old, said negative thoughts can ‘creep up’: “It’s always the kind of thing that’s going to be at the back of your mind, and summer is generally quite a bad time for it.”

This year, the pressure to be in shape for summer is different and perhaps more concentrated than before.

“In the lead-up to summertime, everyone seems to be expecting a glow-up.” Ms Banks said.

Admitting to dealing with body-image issues can feel taboo, but eating disorder charity Beat estimates that some 12.5 million women in the UK suffer from these disorders.

Ms Banks confessed: “I feel like a bad feminist admitting that I’ve had this in the past, but that’s not the case. At the end of the day, it is a mental health disorder and it’s not just a separate thing.”

Mental health professionals have also experienced changes in the amount of people coming forward to seek help and support.

Professor Glenn Waller, an eating disorder specialist at The University of Sheffield, attributed the ‘tsunami of referrals’ for support to those experiencing long-term disorders that have been exacerbated by the lockdowns.

“It’s probably more about people who have struggled for the past year and a half and who got to Christmas and then suddenly couldn’t cope anymore.” the professor said.

Professor Waller recognized that most women have some level of dissatisfaction with their bodies: “We live in a society that really says you’re only valued for being female if you’re the right kind of shape and size.”

The researcher recommended that people accept referrals for support and treatment when they’re available, and highlighted the fact that many methods used for coping are found in prevention. This can be difficult because it’s hard to know exactly when a problem may arise.

“One of the golden rules is you don’t get over an eating disorder long-term unless you deal with the body image issues,” Professor Waller advised.

If you or someone you know is struggling, you can find information and support at Beat and The Centre for Clinical Interventions.